For better or worse (and I would argue from a gardener’s perspective definitely better), many great garden plants including R. cilipenense owe their start to the British aristocracy and by extension the long reach of the British empire.

Leaving the politics of feudal barony, the peerage system, colonialism, and imperialism aside — as Americans we have an equally complicated and problematic history, so a bit of humility is called for — the British horticultural legacy is stunning. And it was indeed an aristocrat, industrialist and politician responsible for both this stunning little beauty of a plant and a magnificent public garden in the north of Wales.

Henry Duncan McLaren, the second Baron of Aberconway is the plantsman credited for the Rhododendron Cilipinense hybrid. Lord Aberconway (in 1923 or thereabouts) named his cross “Cilipinense.” The name is a combination of the parent plants’ species names, R. ciliatum x R. moupinense, resulting in a nomenclature that is a true portmanteau! https://tinyurl.com/5n6b6cae

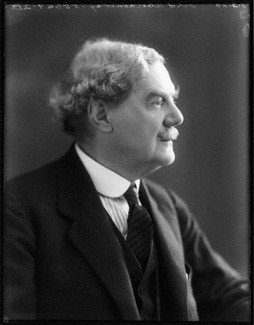

Charles Benjamin Bright McLaren, 1st Baron of Aberconway and father of ‘Cilipenense’ hybridizer Henry Duncan McLaren

But before we get to the plant, let’s digress a bit to look at the history of the family whose estate became Bodnant Gardens, the world-famous garden at Conway in North Wales and now owned by the British National Trust, whose purpose is …”to look after places of historic interest or natural beauty permanently for the benefit of the nation across England, Wales and Northern Ireland.”

According to the National Trust, “…throughout four generations during the family’s stewardship, plants, seeds and cuttings were brought from all over the world to the gardens, many the result of plant-hunting expeditions,” no doubt encouraged and financed by subsequent Barons of Aberconway.

In 1875, Henry Pochin, who was the first Baron of Aberconway’s father-in-law and a successful industrialist and chemist, bought the property of about 80 acres situated above the River Conwy. Pochin may not have envisioned a future botanical wonder, but he was no doubt seduced by the spectacular views of the Snowdonia Mountain Range his new manor offered. He developed some of the initial infrastructure for the gardens, including the fabulous 60-yard long Laburnum archway, which continues to this day.

Apparently Pochin’s son-in-law, Charles Benjamin Bright McLaren, who would become the first Lord of Aberconway, had little interest in horticulture. The son of a politician, Charles was best known for his career in politics and for his work with the companies he inherited from his industrialist father in law Henry.

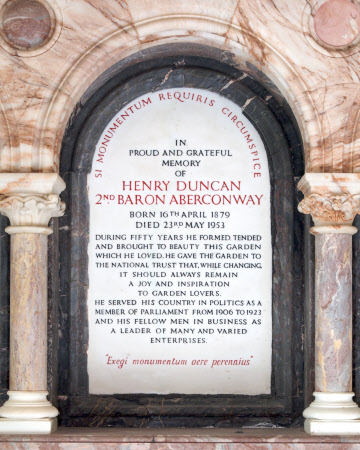

It was the 2nd Baron of Aberconway, Charles son Henry Duncan McLaren, who after a career as both a politician and industrialist, made his mark in the world of horticulture. Henry served as president of the Royal Horticultural Society from 1931 until his death in 1953.

According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online Edition, Oxford University Press, 2004; and the Oxford Dictionary of Business Biography, 5 vols. (1984–6), edited by D. J. Jeremy, Henry Duncan McLaren was a man of considerable creative intellect, “capable of switching his mind from one subject to another with remarkable agility, he drove both himself and others hard. Often considered by contemporaries to be autocratic and difficult to approach, he nevertheless respected sound arguments put forward by others. Imaginative and forward-looking, McLaren resolutely maintained the view that his companies should remain in the forefront of technical progress.”

The Oxford Biographical Dictionary opined that “the range of McLaren’s other interests may well have reduced his overall effectiveness as a businessman.” But it became exceedingly clear that plants and gardening were his great love.”

“Encouraged by his mother, Laura, Henry took advantage of the magnificent property. With great skill and taste he oversaw the design and construction of a magnificent series of terraces, fashioning a wonderful wild garden at the family estate at Bodnant. He planted a wide range of shrubs, and was particularly known for his knowledge and hybridization of rhododendrons. In 1949 he handed over the gardens to the National Trust, along with a generous endowment for their upkeep.”

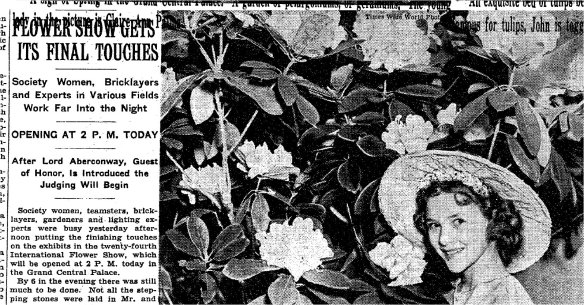

In 1937, Henry traveled to New York as the guest of honor at the 24th International Flower Show, sponsored by the Federated Garden Clubs of New York State and the Garden Club of New Jersey. The New York Times ran a story about the opening of the show on page 25.

After his death in 1953, Henry McLaren was succeeded by his eldest son, Charles Mellvile McLaren, who became the third Baron of Aberconway. Charles was chairman of John Brown & Co. from 1953 to 1978 and of English China Clays from 1963 to 1984, and like his father served as president of the Royal Horticultural Society (from 1961 to 1984).

Charles Melville McClaren died in 2003, but three years before he revealed a rather stunning political secret. His obituary in the Gaurdian Newspaper explained:

“Lord Aberconway, longtime chairman of both John Brown, the Clydeside shipbuilding firm, and English China Clays, and also a master-gardener, has died aged 89. Three years ago, he belatedly unburdened himself of a 60-year-old guilty secret.

He told the Tory historian Andrew Roberts that, as a 26-year-old, he had been one of seven British businessmen dispatched secretly by Neville Chamberlain’s pro-appeasement government to try to stop an Anglo-German war over Poland. Three weeks before the war the seven made their separate ways to the island of Sylt off the German coast, to meet Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering. Their purpose was to offer a “second Munich” – a four-power agreement involving Britain, Germany, France and Italy – to make further concessions to German demands for lebensraum, on condition that the Nazis did not invade Poland.” It should be added that after the secret Sylt conference Germany invaded Poland, and Charles served during the war as an officer in the Royal Artillery.

According to the Gaurdian obituary, “Charles also inherited the presidency of the Royal Horticultural Association, which he held from 1961 to 1983, from his father, and dominated the Chelsea Flower Show for 20 years. These posts were not without problems. He resisted demands for more women on the RHS council. He also fought pressures to allow in guide dogs or make Chelsea more accessible to wheelchairs.”

The Gaurdian obituary continued, …”the third baron made fortnightly weekend visits to the gardens to admire his rhododendrons, even when fully stretched as an industrialist. He would stride around its 60 acres in his knickerbockers, preceded by an immaculately clad butler, with his wife and the head gardener, Mr Puddle, at his side. If Charles was something of a local feudal lord in the Conway Valley – as a big landowner and the high sheriff of Denbighshire since 1950 – he did not have things all his own way. In 1982 he asked to cut down some 60 preserved trees in Prestatyn to build houses on his own land, but was refused permission.”

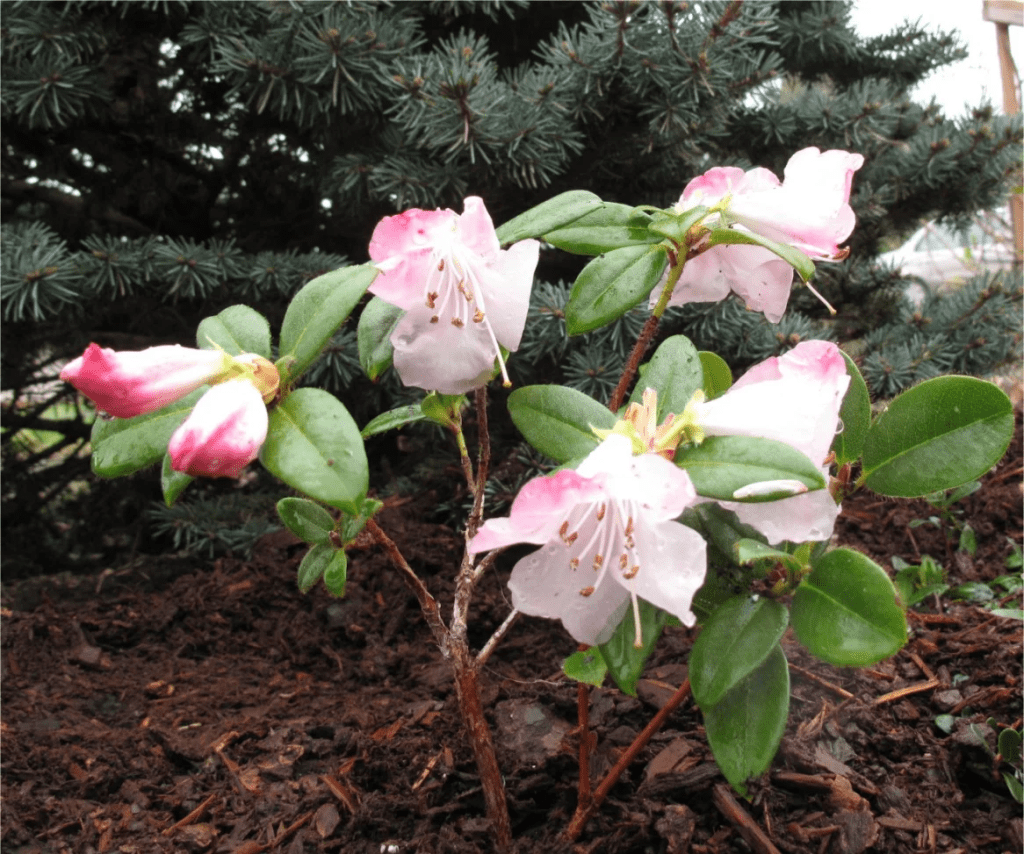

Well then, what about the plant that’s prompted me to dig into all this history? Here are pictures of Cilipenense’s parents. R. ciliatum was the seed-parent and R. moupinense the pollen-parent.

Photo of R. ciliatum by Rollo Adams from the Rhododendron Species Foundation and Botanical Garden in Washington State

According to the Rhododendron Species foundation website. R. ciliatum was first “discovered” in the Sikkim Himalayan region of China. It was subsequently collected from the adjacent mountains of eastern Nepal, Bhutan, and southern Tibet. It is found from 8,000 to 13,000 feet in elevation growing in various habitats including coniferous forests, rhododendron thickets, and open rocky slopes.

R. moupinense is a species native to western Sichuan, China and derives its name from the district of Moupin. First introduced into cultivation by E.H. “Chinese” Wilson in 1909, a notable English plant collector who introduced a large range of about 2000 Asian plant species to the West. (About 60 sixty bear his name). R. moupinense also begins flowering in early spring.

So, with one parent definitely an alpine species, it’s no coincidence that R. cilipenense is reputedly hardy to about 5° Fahrenheit. Cilipinense is slow growing and has more of a rounded rather than an upright habit, and will eventually top out at about three feet after ten or more years.

Here in the Pacific Northwest cilipenense blooms with the hellebores in late February and early March. I planted mine in deeply cultivated soil, taking extra care to put good drainage materials (perlite, pumice and granite chips) in the bottom of the planting hole.

Rhododendron Cilipinense